Tags

analogue versus digital, Animal welfare, Brexit, cult sci-fi, EU, fascism, fiction, fortress Europe, John King, meat is murder, veganism

Is it really twenty years since the immortal advice dispensed more or less at the start of ‘The Football Factory’, but still too late of course for the Coventry ‘diddy man’ in question whose face has just been carved up in a car park?

‘If you want a drink after the game, fuck off out of West London.’

Two decades, and it’s a long way from striping diddy men in car parks to rebel pubs offering a throaty rendition of ‘The ballad of Billy Singh’. Billy, we are told, was a rebel fighter for the shadowy paramilitary organisation GB45, dedicated to the overthrow of centralised EU dictatorship. Welcome to ‘The Liberal Politics of Adolf Hitler’, the eighth novel by cult London author, John King. There’s a hint right there in that cuddly title. If it’s the feelgood factor you’re after, this may not be the right place. And no, before you ask, it doesn’t end at all well for Billy.

The cause Billy was martyred for turns out to be that of the ‘Free English’, a resistance movement which has opted out of the corporatist Europe-wide surveillance state, known collectively as the United States of Europe (USE). The internet (InterZone) is now an all encompassing electronic tag in which every transaction is monitored within what is known as the ‘Troika’. Citizens of the USE are fitted with a special Palm technology which enables even their thought processes to be subjected to the ‘correct’ filters of a new technocratic hierarchy, which it goes without saying is centred in Brussels. Technos, Crats and at the very top of the food chain, Controllers, cast their beady eye on any and all activity which could be construed as ‘suspect’. Such is the totalising nature of this gaze that the only respite is presented in the act of wilful rejection, living off the grid, so to speak, beyond the reach of the otherwise omniscient InterZone. In this dictatorship, refusenik English rebels offer perhaps the clearest example of ‘opting out’. And of course there is a price to be paid for making such a choice. A life lived on the margins haunted by the ever present threat of punitive action by the special-police unit ‘Cool’, or the even more feared ‘Hardcore’ element, mostly devoted to ‘mass rendition’ and the more nightmarish components of the ‘War on Terror’.

It should be clear by now that the author is no fan of the EU. Merkel, Juncker and Cameron amongst others are explicitly named as the story unfolds. And the portrait of metropolitan USE heartlands is distinctly unflattering. The shiny spaces of the ‘New Democracy’ are depicted as sceptic fiefdoms of casual violence and cruelty, in particular to animals, recalibrated as ‘subs’ (subhumans) for the sadistic recreational and gastronomic pastimes of Good Europeans. By contrast, the Free English towns are characterised as much by their veganism and environmentalism as by their hatred for the Brussels’ overlords. It’s quite a leap of faith that’s being proposed here, given the stark picture of meat consumption, cruelty to animals (Countryside Alliance, organised dogfighting anyone?) and hostility or utter indifference to environmental issues which currently describes much of the UK, though interestingly it’s a more mixed picture in the cities. Then again, the choice to set the action in the ‘near future’ helps partially circumvent this difficulty.

What this also does, of course, is raise the intriguing question as to whether this novel was written on the widely held assumption that the Brexit referendum result would not actually come to pass. That might be one way at least of reading the following against the grain:

‘The best lies won. Self-deception was ingrained and perhaps the greatest liars were authors. Novels were produced by the angry and depressed, lonely souls who drank too much and ended up frustrated that their life’s work had changed nothing.’

In the wake of the Brexit vote, though, this makes for uncomfortable reading, particularly given the blatantly false prospectuses put out by both sides, and their toxic aftermath. However, the fallout of those alleged £350million/week, or the 75 million Turks apparently ready at a moment’s notice to clamber up the white cliffs, or the linking of a refugee crisis rather than austerity cuts to the strain on public services, looks set to be with us for a while yet, leaking its slow drip poison into the already muddied wells of the ‘public conversation’. In the space of a few short months we have suddenly been pitched back into a time warp, words like ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘correctness’ spat out like expletives, or should we say ‘cratspeak’? And with far worse than that staining a whole swathe of public life from community cultural centres to the daily commute on public transport.

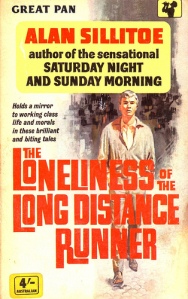

Still, in the near future, those ‘seaside shanties’ and former industrial heartlands which overwhelmingly voted for Brexit, are depicted as being amongst the last remaining outposts for true liberal thought. This is evidently where ‘the Free English commons’ can be found and open debate flourishes. And this is where the novel’s hero, Kenny Jackson lives. Kenny, bookworm, librarian, freedom fighter, is, quite literally, a man on a mission. The journey he makes, from the derided, but ‘free’, periphery back to London, the urban centre where he was born, is a powerful iteration of love, duty and belonging. His presence and motives a tactical riposte to that less charitable view of ‘Little Englanders’ defending hopelessly obsolete fictions of nation and identity. Indeed, there’s a wonderful sub plot involving Kenny, smuggled literature and a trip back in time to a classic working class literary vanguard. In part, Kenny undertakes his perilous mission in the knowledge that literature not only redeems the soul but has the ability to form foundational myths. Of land, self, culture.

This is familiar terrain for King, and ‘The Liberal Politics’ is perhaps at its strongest in this rhapsodic journey through what the novelist, John Lancaster, would describe as ‘Deep England’, though in this case located in the distinctly urban locales of London and Blackpool.

‘Heritage. Cropheads and Jacks. Clockwork youth. Cockney agg.’

It’s gorgeous, and the nod to southeast London in ‘Tiny’s Tup in Catford’ raised more than a smile. The expected Chelsea references are also there, of course. Shed Boy, Eccles and Babs, John Terry (Terry Johns?!). More surprisingly perhaps in a sly amalgam of Chelsea/Millwall underwriting the unrepentant mission statement of the villainous Horace Starski: ‘I know what I am and I don’t care’. And there’s no attempt either to sugarcoat the corporate takeover of ‘the people’s game’. Actual attendance has by this stage largely been dispensed with. Replaced by an advanced 4D ‘virtual’ fandom only available to the lucky few with sufficient ‘credit’ on the Troika system, and what this means in practice is that an ambitious young ‘Crat’ like the Alan B’stard-ish Rupert ‘Rocket’ Ronsberger can for instance engage in a proxy class war while watching a game from the comfort of a corporate pod. His ‘virtual’ hooliganism is personally fulfilling but ventures none of the risk of the real thing. And of course the point is made that this is precisely how the more well heeled have been ‘accessing’ football for some time now in the Premier League era while its traditional working class base has been ushered towards the exits without so much as a prawn cocktail for their troubles.

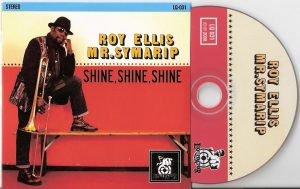

If Kenny is analogue old-school, then Rupert is the epitomé of the digitised present. He is liberal, as in ‘libertarian’, not averse to watching animals being tortured in a night club while having his dick sucked by a specially imported whore. Set against that, the earthier pleasures of the free rebel areas bring welcome respite. Pub sing-alongs, donkey rides at the beach and the magnificent apparition of skinhead reggae stalwart, Roy Ellis and the Moonstompers in Blackpool’s Empress Ballroom. Here too are hen parties and heavy drinking, Bowie on his deathbed, and Indian takeaways. And here’s the ghost of ‘English patriot’, Mickey Patel, forced by Brussels off the end of the pier and ‘back’ to a Gujarat he never knew in the first place.

‘Pure nostalgia. Pure horror. This was England. Part of Britain. Monkey Island.’

That earlier mention of ‘clockwork youth’ is no accident. Beyond the explicit ‘clockwork’ or ‘devotchka’, there’s an evocative rumour of Anthony Burgess in the language King uses – ‘delete’, ‘crush crush’, ‘dirty dumbo’, ‘mentals of porkies’ – most often to signify when ‘subs’ (animals) are being tortured, either for fun or as a prelude to dinner and some more fellatio. Terrified pigs involved in a glasshouse breakout are described as having ‘wee-fronts’ and ‘poo-backs’. As if Alex and his droogs were commandeering the Upton Sinclair classic, ‘The Jungle’. Ordinary folk – the ‘lower commons’ – are sometimes referred to as ‘apes’ and the clubs in which birds, dolphins and dogs are variously tortured to enhance the overall clubbing ‘experience’ for giddy Eurocrats are simply known as ‘Flap!’, ‘Splash!’ and ‘Bark!’.

Again, the novel’s outrage regarding the sadistic maltreatment of animals within ‘New Democracy’, could just as easily describe the routine abuse of animals across the present day UK. For instance, despite being banned for the best part of two centuries, dog fights, in the run up to which cats and kittens are often supplied as bait for the training sessions, are still a daily occurrence.

http://www.league.org.uk/our-campaigns/dog-fighting

http://www.league.org.uk/our-campaigns/racing-animals

And let’s not even get into battery farming or the horrific mass transit conditions endured by millions of animals imported or exported for slaughter. Though of course it’s not just the meat and dairy industries which are to blame. In a disturbing echo of the novel’s clubland scenes, the role played by the leisure industries in contributing to this terrible suffering can hardly be underestimated. Approximately 200 horses die at British racecourses every year and it would be remiss not to point out that the largely working class attraction of Greyhound racing still operates (albeit predominantly in secret) in spite of multiple exposés of the cruelty involved for the dogs. No, it’s not quite in the same league as bullfighting, but it ain’t exactly great.

Try to imagine the rerouting of classic sci-fi – ‘Planet of the Apes’, ‘Westworld’ – via the dystopian prophesies of Orwell, and that’s still not the half of it. There is an uneasy brilliance here, threading a fast receding analogue memory – of vinyl, books, hard currency and, yes, animals – via the nightmarish surveillance state of Hard-Fi’s ‘Stars of CCTV’. The story posits an undeniable warmth in its analogue registers, just people face to face in pubs paying for rounds with cash and listening to proper music, and this is transposed against the bureaucratisation of thought, emotion and certainly language, which are constituent elements of the digitised environment. But this story isn’t about a culture preserved in aspic. Perhaps, in tone, it is closer to the idealism of the eco-survivalists now starting to emerge from the bankrupt ruins of the old Detroit. Understanding that before anyone can move forward, they first have to make their peace with the past, realign themselves with nature and the elemental forces which preceded Motown and its equally elemental collapse. The novel also makes clear that this act of ‘not forgetting’ the time before the corporates is what most terrifies the bureaucrats of the centralising USE. This for example is one of the deepest fears which haunts a key operative.

‘He knew it was unhealthy to look back but panicked at the idea of dying. He had become sentimental. It was terrible. Robotic was best.’

In that sense too the novel might make an intriguing companion piece with the recent fiction of disillusioned environmentalist, Paul Kingsnorth (‘Beast’, ‘The Wake’). Or in its brutality and maybe unexpected humanism with the art of ‘The New Barbarians’, Tim Noble and Sue Webster, of whom Michael Bracewell once wrote the following:

‘In the imagery of decay, violent death and destruction, honed with wit and tempered with sentimentality, this was the imagery of romantic nihilism.’

Yes it’s been twenty years and a lot’s changed since then. Make no mistake, this is a poetic and intensely humane howl from ‘the commons’. It would take a heart of stone not to hear that. But ‘The Liberal Politics’ is still a bit like being kicked in the gut and then offered a pint straight after. And strangely enough, that turns out to be a good thing. Viddy, viddy good.

#