Tags

Black and Blue, Black footballers, Chelsea Football Club, Mental Health, music, Paul Canoville, racism in football, Roy Ayers, Southall, The Paul Canoville Foundation

‘Yeah, we know they’re skilful, but they don’t track back. Never put a shift in. They don’t like it up ‘em. Not good in the mud. And that’s the point. All well and good playing samba football at the weekend, but can they hack it on a cold and wet Tuesday up in Stoke?’

#

Do you remember those days? Maggie, and the Miners, and shit telly and even shitter attitudes? The stereotypes, always foolish, about black footballers, but clung onto anyway by far too many ‘footballing people’ for way too long, pretty much all exploded in one glorious half of down-but-not-quite-out bravado. And aptly enough on a cold Wednesday night up in Sheffield. Jan 30, 1985. Not Stoke, but near enough.

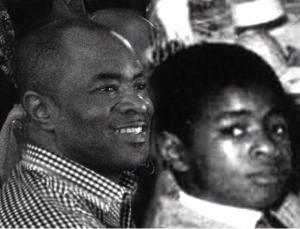

A goal with his first touch, another, which ought to have been the winner (and on any other night might well have been) with full-time beckoning, sealing a remarkable comeback by Chelsea in that year’s Milk Cup quarter final. Mention Paul Canoville to anyone who remembers football in the pre-Premier League era, and that’s the memory that’ll most likely surface. Chelsea, run ragged in the first half at Hillsborough. 3-0 down at half-time. Canoville, affectionately known as ‘Canners’, coming on as the second-half sub and transforming the game. And yes, that’s the sub. Only one substitution permitted back then, yet another indication of how much the game has changed since that time. Typically, for a life being lived with an unusual intensity, the post-match debrief in the Players’ Bar would also mark the first time Canners had seen his father in twenty-one years! A lot to take in for the kid from Southall, whose young life had already seen more than its fair share of drama.

The raw facts are these. Paul Canoville – ‘Canners’ – born in 1962 in Southall. Signed for Chelsea in December 1981 before making his first team debut, coming on as a sub, in April 1982. Five years at Chelsea in which he made over 100 appearances, scoring 15 goals and playing a key role in the club’s promotion to the top tier as Second Division winners in 1984 and to a Full Members Cup in 1986. Another successful stint followed at Reading before his career was curtailed by injury aged just 25. But sometimes the facts don’t give you the full picture. And in Canners’ case, they don’t even come close.

Take that debut, against Palace at Selhurst Park. What should have been one of the proudest moments of any young player’s life, marred instead by the shocking racial abuse he received from what turned out to be his own fans! ‘We don’t want the nigger!’ ‘Black cunt!’ ‘Sit down, you wog!’ just a sample of the ugliness on display that evening. Though it’s been 35 years, and so much has happened in his own life, and in the broader cultural environment of football, since then, the hurt, into which some of the anger must have morphed, is still evident. He looks unfeasibly well on his five and a half decades, but even now the memory of that night unspools as something raw.

‘I could hear it when I was doing my stretches. But it’s when I turned around and saw it wasn’t Palace supporters, but Chelsea giving me all that grief. That came as a shock.’

But the abuse continued long after his debut and at one point got so bad that Canners cut short his own pre-match warm-up at Stamford Bridge. ‘I never looked directly at the ones giving me the grief, though I could hear it. That’s the thing, if I’d made eye contact, then I couldn’t have left it at that. I’d have had to confront them, had it out with them.’

Of course Canners would go on to become a favourite for many at Chelsea. Their first black player, a pacy, powerful midfielder whose mazy runs and occasionally brilliant finishing instilled panic in more than a few formerly impervious defences. To see how far, and in what ways, the club, and the culture, have developed since then, it’s extraordinary to think it was only forty odd years ago that even the prospect, let alone the reality, of black footballers was anathema to a club like Chelsea, and to so many others. Now it’s inconceivable that a team could compete without black players, though the ongoing dearth of Asian footballers and black managers, and near-total absence of black faces at boardroom or executive level emphasize some of the challenges the game still faces. Things have clearly moved on though since the time that Canners signed for Reading, back in 1986. ‘So I turn up at the chairman’s house. When the door opens it’s his daughters standing there. And they scream when they see me. I’m thinking, ‘sod this’, and I’m about to go when the chairman, Ian Branfoot, who’d heard the screaming, rushed to the front door and couldn’t have been any more apologetic when he saw me. “It’s ok, Paul. It’s ok. I’m really sorry about that, but don’t take it personally. It’s just that they’ve never met a black man before.”’

He chuckles at the memory, the gap between innocence and intent the detail which stands out. Laughs again recalling perhaps his finest hour, the 4-4 at Sheffield Wednesday. The whole first half, when he was sat in the dugout with Keith ‘Jonah’ Jones, a Wednesday supporter had been goading the pair of them, handing them sweets as the home side took the lead, and then went further ahead. So when Canners got his second, and Chelsea’s fourth, close to the end, he knew exactly how he wanted to celebrate. ‘People think I ignored Kerry (Dixon) and was giving it the black power salute, but the truth was I ran straight back towards the dugout to see if I could find that woman who’d been taking the mickey. I couldn’t see her though. Mind you, Jonah said she’d piped down in the second half anyway. Quiet as anything once our equaliser went in.’

Many of the good times seem to be from that period in the mid-eighties, by which point he was a first team regular and Chelsea had won promotion back to the First Division. The opening fixture of that season, Canners distinguishing himself in his First Division debut against Arsenal. ‘I had a kriss haircut before the game, and then ‘nuff respect from all the Hackney Gooners after. I used to live in that area, and most of my mates were Gooners, but after that game, at Highbury, even people I didn’t know were coming up to me in the street, at the barber’s, shaking my hand.’

A snappy dresser, the provenance of the ‘King Canners’ moniker, and all round man-about-town, with many of the outward trappings of success. Fame, fast cars, adulation. Yet this was still, at heart, the same kid who remembered seeing Laurie Cunningham trap a ball mid-air during one of the many laissez-faire matches that used to sprawl across Hackney Marshes in the seventies. The same kid who apparently, even as a baby, never crawled, just ran. The same kid who remembered ‘bussing’ in late 1960s Southall. (The result of the racist Southall Residents’ Association, which vehemently opposed integrated schooling). And yes, that’s Southall, Middlesex, not South Carolina! The same kid who, reflecting back on that time, now sees the myriad ways he was ‘emotionally impaired’ by his environment, and how much a lack of maternal affection has affected him throughout his life. But as he says himself in his disarmingly honest memoir, ‘Black and Blue’: ‘To forget is not an option’.

He can be as funny in print as he is in person. At one point, describing a (very) brief teenage conversion to Rastafarianism, he concedes. ‘I was as steadfast as the most righteous Dread for two weeks at least. Then the lure of Mum’s Saturday morning fry-ups grew too much and bacon was very much back on the menu. The trainee Rasta copped out.’

He admits he was something of a ‘fallyman’ (follower) in his early teenage years, once he’d fallen in with a group of older boys who effectively inducted him into the Black British culture of the time. He describes himself as ‘a child leading a man’s life’, so perhaps it’s not that surprising that he lost his virginity at 14 to a woman twice his age. This was the time of sound systems like Fatman or Mellotone, of bands like Burning Spear and Culture. The big tunes of that moment, the ones Canners recalls, are Louisa Mark’s ‘Keep it like it is’ and Barry Biggs’ ‘Wide Awake in a Dream’. It’s roughly when ‘Roots’ was first shown on British television and even if he was still a child, he admits: ‘It made me realise that there was a struggle going on out there, and I had no choice about what side I was on.’ This is also the Southall of racist policing and National Front activity, later of the SPG and Blair Peach. A place of dread. The SUS laws and getting bushwhacked after dark. It is both the body of Gurdip Singh Chaggar and the wayward trajectory of the fallyman. Led astray by those around him, on the rob, and let down by his own judgement. A spell in borstal. Above all, left broken-hearted by his first babymother, Christine, an episode which clearly still rankles.

‘I wanted to be there for her, for Christine, and our kid. But she turned away from me, wouldn’t let me. And that really hurt me back then. Bear in mind I was still very young, and just out of borstal. That hit me really hard. It’s only years later when I was in rehab, and I was forced to dig really deep and let things out, that I realised the effect that had on me. I was different after Christine.’

The fallyman became something of a ‘playa’, a ‘gyallist’. Underscoring much of it, though, a lack of everyday stability, involving stints of homelessness during which Canners slept in an abandoned car. In fact just two days before his Chelsea debut he was homeless again! Those complicated shadows would continue to be cast over his personal and professional life long after ‘King Canners’ first cut a dash on the Chelsea team coach in his Pierre Cardin, Cecil Gee, snakeskin shirt and croc skin shoes. The Sticksman style utterly at odds with the more pedestrian tastes of his team-mates, at Chelsea and beyond. As were the reggae, jazz-funk, hip hop mixtapes he favoured. A kindred, of sorts, emerged in the figure of Pat Nevin, the midfield dynamo in that mid-80s side, and a fellow music-nut, though with very different tastes. Also the only Chelsea player from that side to openly declare his disgust with the racist treatment being meted out to his friend and team-mate. There is genuine feeling when Canners mentions Nevin, and other individuals such as John Drewitt, a season-ticket holder who took a stand against the racism he witnessed in the West Stand. But the fact remains, there was a portion of the Chelsea faithful who were still only prepared to accept Canners on their terms. Recalling a tackle he made on Luther Blissett, the memory is bittersweet. ‘The realisation that I had to kick a black boy to hear them call my name. It was as if I’d had to do that to get acceptance. They were seeing me finally as one of them.’

Worse, those attitudes were never limited to the terraces. The changing room was hardly exempt. ‘There were lots of white bigots around and some of them became footballers, as I discovered.’

In 1986, Canners was racially abused and then attacked with a golf club by one of his own team-mates! Yet in a textbook replica of wider social attitudes, it was Canners, rather than the abuser, who found himself frozen out at Chelsea and looking for a new contract elsewhere. His shameful treatment by the club make his partial, much later readmission within the Chelsea fold seem all the more remarkable. The day we meet, it’s at his place, within a spit of Stamford Bridge. His eyes light up when he mentions the reserves, and the youth teams coming through at the club.

‘Nine black players on the pitch last night, bruv. And they were controlling the game. And you know what, these are black British boys. London boys.’

Mercifully it’s a far cry from his own introduction to the club. That journey started out in a very different place, one marked by shadows. Withheld affection, the brittle contusions of young love. The shell hardening, the styles broadening. Fatman and Mellotone, but also Contempo and Crackers. Soul, funk, reggae and plenty flash. But behind the sounds, a young man who as he readily admits, was ‘totally unprepared for life outside the game.’ One game replacing another, flesh and foul. After the adulation, the comedown. Life after football. The need for something more from the original raver, the soundman who’d come a long way from Southall.

A second life as a DJ on the rare groove sound system, ‘GQ’. Canners as one of the ‘three wise men’ brewing up a not-so-quiet storm in late 80s Hackney. Big tunes and a big system, a big reputation with the ladies too.

And then in 1991, crack. Meeting the devil for the first time under the arches in Vauxhall.

‘Crack and being civilized don’t go together very well though.’

The descent was rapid. Forced to sell his much prized record collection for a pittance to finance his crack habit, and in his own words, ‘Now I’d sold off my tunes for drugs and lost control, I was a shadow of a man.’ But rockbottom was yet to come, though wearing Reeboks was a sure sign that it was on its way. When it hit, though, the despair it must have brought in its wake is unimaginable. And suddenly Canners was no longer that man, but a fiend in thrall to the rock. His baby son died in his arms and right after he stole from the babymother and got wasted on crack. Detox, rehab and then the cancer diagnoses (there have been two) mark some of the grimmest episodes in a life which finally seemed to have bottomed out. At various points in his memoir, there are frank admissions of how low he’d sunk. Compared to women, ‘the least complicated relationship I ever had was with crack. It is evil, it ruins our lives but we love it.’ And that from a self-confessed ‘gyallist’, with eleven children from ten babymothers! Elsewhere the painful process of rehab, but also the depth from which recovery begins, is hinted at. ‘I was starting to crawl from the wreckage of my life. It was like a workout for my soul.’ To subsequently be diagnosed with cancer (twice), and to successfully come back from those diagnoses both times, is little short of remarkable. Recovering from a course of chemo, Chelsea’s first black player had to watch from his hospital bed in 1997 as Chelsea’s first black manager, Ruud Gullit, led them out at Wembley to FA Cup success.

With the beast of sickness in abeyance, yet another incarnation emerged from its shadows: this time Canners as a youth worker, gradually morphing into first a teaching assistant and then a motivational speaker, setting up his own foundation and working to raise awareness of mental health issues, especially in young lives. A healthy-again Canners is once more the livewire of legend, though it’s clear there’s bitter experience just past the jocular surface. This man who outflanked all his opponents, including the invisible ones, still here, still fighting the good fight. Given everything else that is currently going on in our society, the resurgent racism, the intolerance, his story, in all its guises, ought to resonate centre-stage. Paul Canoville. Trailblazer, Icon. Casualty. Inspiration.

Time Added On

There is a moment in the Roy Ayers’ classic ‘Running Away’ when the vibesman really goes to work and the social despair of 1977 is recast as fluid, black modernism. Picture the scene. Hackney Marshes, or some other ancient London lung. A young black kid traps the ball midair and then goes on one of those mazy runs he was already getting a rep for. Except this time it’s not Laurie. This time the kid’s called Paul and mercifully, unlike poor Laurie, he’s still with us. The first.

Nice one Ko…we’ve come a long way, and not very far at all.

LikeLike